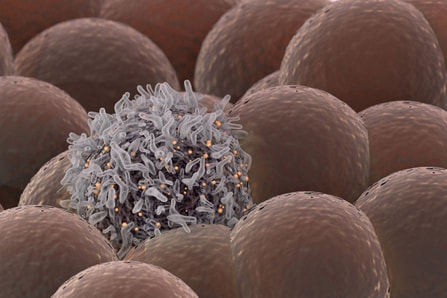

Stanford University researchers have discovered a new cellular signal that cancer cells seem to use to evade detection and destruction by the cells of the immune system, and macrophages in particular. Studies by the team of researchers in mice model paved a way for development of new therapeutic strategies. The scientists have shown that blocking this signal in mice implanted with human cancers allows immune cells to attack the cancers. Cancer cells have shown in earlier studies, that they choose to evade destruction by macrophages by overexpressing anti-phagocytic surface proteins called ‘don’t eat me’ signals such as CD471, programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and the beta-2 microglobulin subunit of the major histocompatibility class I complex (B2M). Antibodies that block CD47 are in clinical trials. Cancer treatments that target PD-L1 are already being used in the clinics. The study lead by Amira Barkal, an MD-PhD student, (lead author). Irving Weissman, MD, professor of pathology and of developmental biology and director of the Stanford Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine (senior author), showed that CD24 can be the dominant innate immune checkpoint in ovarian cancer and breast cancer, and is a promising target for cancer immunotherapy.Looking for additional signalsThe scientists began by looking for proteins that were produced more highly in cancers than in the tissues from which the cancers arose. “You know that if cancers are growing in the presence of macrophages, they must be making some signal that keeps those cells from attacking the cancer,” Barkal said. “You want to find those signals so you can disrupt them and unleash the full potential of the immune system to fight the cancer.” The search showed that many cancers produce an abundance of CD24 compared with normal cells and surrounding tissues. In further studies, the scientists showed that the macrophage cells that infiltrate the tumor can sense the CD24 signal through a receptor called SIGLEC-10. They also showed that if they mixed cancer cells from patients with macrophages in a dish, and then blocked the interaction between CD24 and SIGLEC-10, the macrophages would start gorging on cancer cells like they were at an all-you-can-eat buffet. “When we imaged the macrophages after treating the cancers with CD24 blockade, we could see that some of them were just stuffed with cancer cells,” Barkal said. Lastly, they implanted human breast cancer cells in mice. When CD24 signaling was blocked, the mice’s scavenger macrophages of the immune system attacked the cancer. Of particular interest was the discovery that ovarian and triple-negative breast cancer, both of which are very hard to treat, were highly affected by blocking the CD24 signaling. “This may be a vulnerability for those very dangerous cancers,” Barkal said. Complementary to CD47?The other interesting discovery was that CD24 signaling often seems to operate in a complementary way to CD47 signaling. Some cancers, like blood cancers, seem to be highly susceptible to CD47-signaling blockage, but not to CD24-signaling blockage, whereas in other cancers, like ovarian cancer, the opposite is true. This raises the hope that most cancers will be susceptible to attack by blocking one of these signals, and that cancers may be even more vulnerable when more than one “don’t eat me” signal is blocked. “There are probably many major and minor ‘don’t eat me’ signals, and CD24 seems to be one of the major ones,” Barkal said The researchers now hope that therapies to block CD24 signaling will follow in the footsteps of anti-CD47 therapies, being tested first for safety in preclinical trials, followed by safety and efficacy clinical trials in humans. For Weissman, the discovery of a second major “don’t eat me” signal validates a scientific approach that combines basic and clinical research. “These features of CD47 and CD24 were discovered by graduate students in MD-PhD programs at Stanford along with other fellows,” Weissman said. “These started as fundamental basic discoveries, but the connection to cancers and their escape from scavenger macrophages led the team to pursue preclinical tests of their potential. This shows that combining investigation and medical training can accelerate potential lifesaving discoveries.” References: 1. Original article: Stanford University of Medicine Note: The article has been edited for style and length 2. Journal article: Amira A. Barkal, Rachel E. Brewer, Maxim Markovic, Mark Kowarsky, Sammy A. Barkal, Balyn W. Zaro, Venkatesh Krishnan, Jason Hatakeyama, Oliver Dorigo, Layla J. Barkal, Irving L. Weissman. CD24 signalling through macrophage Siglec-10 is a target for cancer immunotherapy. Nature, 2019; DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1456-0 3. Image source: Stanford University of medince

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorHello! My name is Arunabha Banerjee, and I am the mind behind Biologiks. Leaning new things and teaching biology are my hobbies and passion, it is a continuous journey, and I welcome you all to join with me Archives

July 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed