The beginning of a long quest

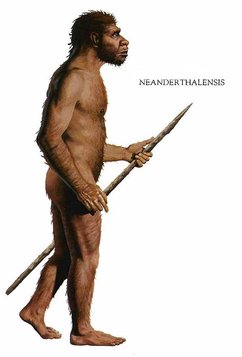

It was the year 1856 when few limestone excavators working near Düsseldorf, Germany, unveiled bones that resembled to humans and initial analysts inferred them as belonging to a deformed human, citing their oval shaped skull, with a low, receding forehead, distinct brow ridges, and bones that were unusually thick. It was only subsequent studies that revealed that the remains belonged to a previously unknown species of hominid, or early human ancestor, that was similar to our own species, Homo sapiens. In 1864, the specimen was dubbed Homo neanderthalensis, after the Neander Valley where the remains were found.Neanderthals rose to prominance around 200,000 and 250,000 years ago and ruled the hills and grasslands of europe till extiction around 30000 years ago. The exact date of their extinction had been disputed but in 2014, a team led by Thomas Higham of the University of Oxford used an improved radiocarbon dating technique on material from 40 archaeological sites to show that Neanderthals died out in Europe between 41,000 and 39,000 years ago, with the last group disappearing from southern Spain 28,000 years ago. Similarity of Neanderthals with Rhodesian Man (Homo rhodesiensis) made early investigators infer that they share similar ancestor but comparison of the DNA of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens suggests that they diverged from a common ancestor between 350,000 and 400,000 years ago, which some argue might be Homo rhodesiensis but this argument assumes that H. rhodesiensis goes back to around 600,000 years ago. However one can not rule out convergent evolutionary paths for the two hominids displaying feathres such as distinct brow ridges. Neanderthals settled in Eurasia, but not extending beyond modern day Israel. No neanderthal sites were observed in the African continent and Homo sapiens appears to have been the only human type in the Nile River Valley because of the warmer climate present in that period. Are Neanderthals really extinct? Sudden disappearnce of Neanderthals from Europe co-incides with the arrival of H. sapiens and this information prompted many scientists to suspect that the two events are closely linked, and humans contributed to the demise of their close cousins, either by outcompeting them for resources or through open conflict. The hypothesis that early humans violently replaced Neanderthals was first proposed by French palaeontologist Marcellin Boule (the first person to publish an analysis of a Neanderthal) in 1912. However according to a 2014 study by Thomas Higham and colleagues based on organic samples suggest that the two different human populations shared Europe for several thousand years. Therefore outright violent extinction seems less plausible and leads to the formation of two scenarios for Neanderthal extinction. Possible scenarios for the extinction of the Neanderthals are:

Ancient DNA to the rescue

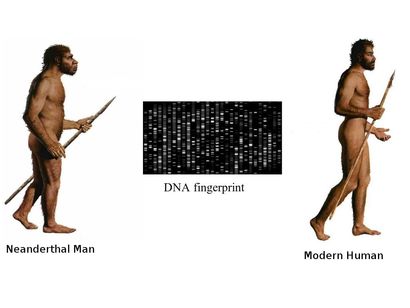

DNA sequence analysis of the fossils can reveal an entirely new world of information to us, but recovering DNA from samples that are fossilized thousands of years ago, is a daunting task in itself making ancient DNA research far from routine. The samples are prone to degradtion and contamination by DNA from other sources, and retriving data out of the ancient material is costly and painstaking work. At a more fundamental level, it requires determining whether the necessary samples even exist and, if so, how to get access to them. The revelations An international group of Anthropologists from Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Cold Spring Harbour Laboratories and Cornell University using various different methods of DNA analysis estimated an interbreeding to have happened less than 65,000 years ago, around the time that modern human populations spread across Eurasia from Africa. They reported evidences for a modern human contribution to the Neanderthal genome. Martin Kuhlwilm, co-first author of the new paper, identified the regions of the Altai Neanderthal genome sharing mutations with modern humans. They found evidences of gene flow from descendants of modern humans into the Neanderthal genome to one specific sample of Neanderthal DNA recovered from a cave in the Altai Mountains in southern Siberia, near the Russia-Mongolia border. Earlier studies have observed that DNA of modern humans contains 2.5 to 4 percent Neanderthal DNA. However studies conducted by Mendez et. al. revealed that no Neanderthal Y chromosomal DNA was ever observed in any human sample they have tested. Contemplating upon the observations they initially felt that the Neanderthal Y chromosome genes could have drifted out of the human gene pool by chance over the millennia, or there are possibilities that the Neanderthal Y chromosomes include genes that are incompatible with other human genes. Mendez, and his colleagues have found evidence supporting this idea, and they think that the two groups may have been reproductively isolated unlike thought earlier. Their study identified protein-coding differences between Neandertal and modern human Y chromosomes. Changes included potentially damaging mutations to PCDH11Y, TMSB4Y, USP9Y, and KDM5D, and three of these changes are missense mutations in genes producing male-specific minor histocompatibility (H-Y) antigens. Antigens derived from KDM5D, for example, are thought to elicit a maternal immune response during gestation. It is possible that these incompatibilities at one or more of these genes played a role in the reproductive isolation of the two groups. Thus Y-chromosomal studies have re-drawn the time-line of divergence of the two species ~4 million years ago, which according to previous estimates based on mitochondrial DNA put the divergence of the human and Neanderthal lineages at between 400,000 and 800,000 years ago. New data emerging out of GWA studies could shed further light on the evolutionary history of the two hominids. In my opinion the image could resolve better if we look into the pathogen associated and immune response genes that we might have inherited or acquired during our evolutionary journey. Reference:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorHello! My name is Arunabha Banerjee, and I am the mind behind Biologiks. Leaning new things and teaching biology are my hobbies and passion, it is a continuous journey, and I welcome you all to join with me Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed